Russian wheat after the failure of the Black Sea initiative has risen in price to 240 dollars per ton. The blocking of Ukrainian ports may provoke a further rise in prices. But a record harvest and stockpiles are allowing Moscow to increase exports and humanitarian aid to the poorest countries. Kyiv, meanwhile, is looking for workarounds. About the situation on the grain market - in the material RIA Novosti.

Patience snapped

Russia perceived the grain deal as a humanitarian mission and repeatedly extended it, despite the fact that the West did not fulfill its obligations. The grain promised to the poorest countries was sent to Europe, while Africa received less than three percent, Vladimir Putin noted.

The world market reacted violently to the missile attacks on targets in the ports on the Danube and in Odessa. According to the Rusagrotrans analytical center, Russian wheat added $12.5 per ton, American - $12, French - $19. Experts believe that domestic exports in July may break the record of four million tons. Tariffs for domestic shipping have also increased, however, mainly for deep-water ports.

Industry analysts consider it all an emotional reaction. "Sea routes for Ukraine are practically cut off, which means that transportation will cost Kiev much more, which will not allow artificially lowering prices," says Arkady Zlochevsky, president of the Russian Grain Union (RGU). "However, there are no grounds for a systemic rise in prices." The harvest is good and production exceeds consumption. Nevertheless, the end of dumping in the Black Sea basin will keep the market from falling. "Grain will become cheaper, but not much," the expert clarifies.

The International Monetary Fund still predicts a rise in prices by ten to fifteen percent.

According to financial analyst Mikhail Belyaev, the wheat boom is only the beginning. Other cultures will join. "The basis of Ukrainian exports is corn, ten to fifteen percent of the world market. This is quite enough for the price to increase by at least ten percent. More likely, 20-25 percent," he argues.

At the same time, Zlochevsky points out that the production capacities of the United States, Argentina and Brazil are many times greater than those of Ukraine, and these players will easily replace the 20 million tons of corn that fell out.

The ripple effect

Eritrean envoy to the UN Sophia Tesfamariam said the grain deal did not solve the problem of hunger, but was just "a good way to blame the Russians, taking advantage of the Africans."

For his part, Vladimir Putin assured that Moscow is ready to give free grain to the poorest states.

"Of course, we are not talking about all deliveries to Africa (and 20-30 percent of exports go there)," says Zlochevsky. "But Russia is capable of replacing all humanitarian aid from international organizations." This can be done in two ways: the state will either buy the required amount of grain from the producers, or borrow from the intervention fund. "There are three million tons, and the previous subsidies did not exceed half a million," the expert clarifies.

At the Russia-Africa summit, the President announced that in the next three to four months Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe, Mali, Somalia, the Central African Republic and Eritrea will receive 25-50 thousand tons of grain.

“But the difficulty is not only in the route. The African transport network is very weak, many entry points for cargo to the continent will be required,” Belyaev adds.

Who will help

Meanwhile, Ukraine is looking for alternative routes. The agricultural sector there is one of the few industries that continue to operate and allocate funds to the budget. “This is about 80 billion dollars, and 40-50 gave grain,” Belyaev explains. To lose almost the last item of income is very painful for both the Kyiv regime and its Western patrons. Even wealthy Europeans cannot afford to feed 30 million people.

“We are working with our EU allies, we are working with Ukraine and other partners in Europe to see if there are ways to get grain to markets by land,” said John Kirby, strategic communications coordinator at the White House National Security Council. At the same time, he acknowledged that in terms of efficiency this cannot be compared with maritime transport.

The Balts offered their ports, but the common borders with Ukraine They dont have. “It will have to be transported by highways or railways through Poland. It will turn out to be too expensive. In addition, the throughput is limited there. So this idea is unlikely to lead to success,” Belyaev believes.

However, not everyone in Europe is worried about Kyiv's problems. In particular, Poland, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Hungary and Romania demand from the EU Council to extend the ban on the import of Ukrainian food into their territory until the end of the year. This will make transport even more difficult.

The Ukrainian Grain Association (UGA) is also trying to negotiate with Moldova on the creation of a green corridor to the Danube river ports through the village of Palanki. However, Moldovan agrarians are going through hard times without this. The Power of Farmers Association said the ports are very slow, with trucks waiting in line for five to six days, and delays have to be compensated by price cuts.

The Minister of Agriculture even spoke about the introduction of a state of emergency, and the country's authorities promised to support farmers. It seems that more and more states are forced to solve internal problems and are in no hurry to help Ukraine to the detriment of their own interests.

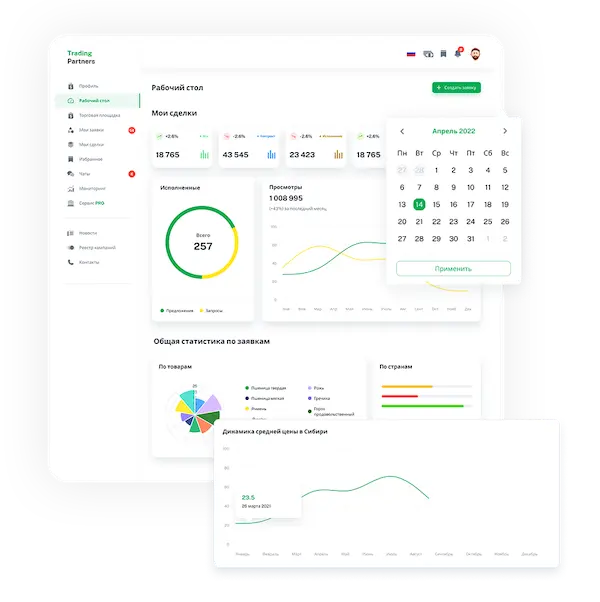

Trading platform

Trading platform

Monitoring

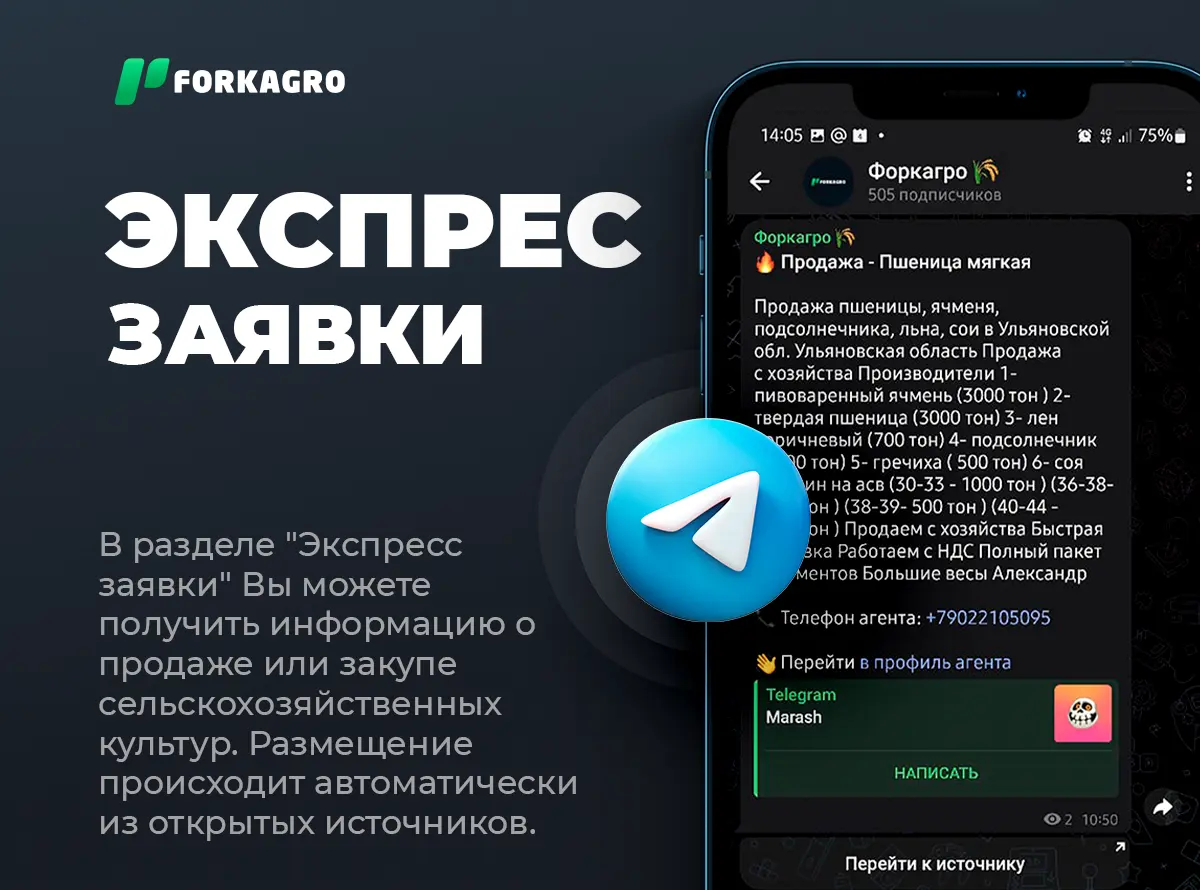

Monitoring  Express applications

Express applications

Fork Work

Fork Work

Service

Service  News

News  Directory

Directory